Important Classes - Time

Unity’s Time class provides important basic properties that allow you to work with time-related values in your project.

This page contains explanations for some more commonly used members of the Time class, and how they relate to each other. You can read individual descriptions for each member of the time class on the Time script reference page.

The Time class has a few properties which provide you with numeric values that allow you to measure time elapsing while your game or app is running. For example:

-

Time.timereturns the amount of time in seconds since your project started playing. -

Time.deltaTimereturns the amount of time in seconds that elapsed since the last frame completed. This value varies depending on the frames per secondThe frequency at which consecutive frames are displayed in a running game. More info

See in Glossary (FPS) rate at which your game or app is running.

The Time class also provides you with properties which allow you to control and limit how time elapses, for example:

-

Time.timeScalecontrols the rate at which time elapses. You can read this value, or set it to control how fast time passes, allowing you to create slow-motion effects. -

Time.fixedDeltaTimecontrols the interval of Unity’s fixed timestepA customizable framerate-independent interval that dictates when physics calculations and FixedUpdate() events are performed. More info

See in Glossary loop (used for physics, and if you want to write deterministic time-based code). -

Time.maximumDeltaTimesets an upper limit on the amount of time the engine will report as having passed by the “delta time” properties above.

Variable and Fixed time steps

Unity has two systems which track time, one with a variable amount of time between each step, and one with a fixed amount of time between each step.

The variable time step system operates on the repeated process of drawing a frame to the screen, and running your app or game code once per frame.

The fixed time step system steps forward at a pre-defined amount each step, and is not linked to the visual frame updates. It is more commonly associated with the physics system, which runs at the rate specified by the fixed time step size, but you can also execute your own code each fixed time step if necessary.

Variable frame rate management

The frame rate of your game or app can vary because of the time it takes to display and execute the code for each frame. This is is affected by the capabilities of the device on which it is running, and also on the varying amount of complexity of the graphics displayed and computation required each frame. For example, your game may run at a slower frame rate when there are one hundred characters active and on-screen, compared to when there is only one. This variable rate is often referred to as “frames per second”, or FPSSee first person shooter, frames per second.

See in Glossary.

Unless otherwise constrained by your quality settings or by the Adaptive Performance package, Unity tries to run your game or app at the fastest frame rate possible. You can see more details of what occurs each frame in the execution order diagram, in the section marked “Game Logic”.

Unity provides the Update method as an entry point for you to execute your own code each frame. For example, in your game character’s Update method, you might read the user input from a joypad, and move the character forward a certain amount. It’s important to remember when handling time-based actions like this is that the game’s frame rate can vary and so the length of time between Update calls also varies.

Consider the task of moving an object forward gradually, one frame at a time. It might seem at first that you could just translate the object by a fixed distance each frame:

//C# script example

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class ExampleScript : MonoBehaviour {

public float distancePerFrame;

void Update() {

transform.Translate(0, 0, distancePerFrame); // this is incorrect

}

}

However with this code, as the frame rate varies, the the object’s apparent speed also varies. If the game is running at 100 frames per second, the object moves distancePerFrame one hundred times per second. But if the frame rate slows to 60 frames per second (due to CPU load, say) then it only steps forward sixty times a second and therefore covers a shorter distance over the same amount of time.

In most cases this is undesirable, particularly with games and animation. It is much more common to want your in-game objects to move at steady and predictable speeds regardless of the frame rate. The solution is to scale the amount of the movement each frame by the amount of time elapsed each frame, which you can read from the Time.deltaTime property:

//C# script example

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class ExampleScript : MonoBehaviour {

public float distancePerSecond;

void Update() {

transform.Translate(0, 0, distancePerSecond * Time.deltaTime);

}

}

Note that the movement is now given as distancePerSecond rather than distancePerFrame. As the frame rate varies, the size of the movement step will vary accordingly and so the object’s speed will be constant.

Depending on your target platform, use either Application.targetFrameRate or QualitySettings.vSyncCount to set the frame rate of your application. For more information, see the Application.targetFrameRate API documentation.

Fixed Timestep

Unlike the main frame update, Unity’s physics system works to a fixed timestep, which is important for the accuracy and consistency of the simulation. At the start of the each frame, Unity performs as many fixed updates as necessary to catch up with the current time. You can see more details of what occurs during the fixed update cycle in the execution order diagram, in the section marked “Physics”.

You can also execute your own code in sync with the fixed timestep, if necessary. This is most commonly used for executing your own physics-related code, such as applying a force to a RigidbodyA component that allows a GameObject to be affected by simulated gravity and other forces. More info

See in Glossary. Unity provides the FixedUpdate method as an entry point for you to execute your own code each fixed timestep.

The fixedDeltaTime property controls the interval of Unity’s fixed timestep loop, and is specified in seconds. For example, a value of 0.01 means each fixed timestep is one hundredth of a second in duration, and so there will be 100 fixed time steps per second.

If your game or app is running at a higher frame rate than the number of fixed timesteps per second, it means each frame duration is less than the duration of a single fixed timestep. In that case, Unity performs either zero or one fixed physics updates per frame. For example, if your fixed timestep value is 0.02, there will be 50 fixed updates per second. If your game or app then runs at 60 frames per second, approximately one in ten frames will not have a fixed update.

If your game or app is running at a lower frame rate than the fixed timestep value, it means each frame duration is longer than a single fixed timestep. To account for this, Unity will perform one or more fixed updates each frame, so that the physics simulation catches up with the amount of time elapsed since the last frame. For example, if your fixed timestep value is 0.01, there will be 100 fixed updates per second. If your app runs at 25 frames per second, Until performs four fixed updates every frame. You might want a scenario like this where it’s more important to model more accurate physics than to have a high frame rate.

You can read or change the duration of the fixed timestep in the Time window, or from a script using the Time.fixedDeltaTime property.

Note: A lower timestep value means more frequent physics updates and more precise simulations, which leads to higher CPU load.

Unity’s Time Logic

The following flowchart illustrates the logic that Unity uses to count time in a single frame, and how the time, deltaTime, fixedDeltaTime, and maximumDeltaTime properties relate to each other.

Controlling and handling variations in time

As described above, there can be variations in the amount of time elapsed between each frame.

Elapsed time variations can be slight. For example, in a game running at 60 frames per second, the actual number of frames per second may vary slightly, so that each frame lasts between 0.016 and 0.018 seconds. Larger variations can occur when your app performs heavy computations or garbage collection, or when the resources it needs to maintain its frame rate are being used by a different app.

The properties explained in this section are:

- Time.time

- Time.unscaledTime

- Time.deltaTime

- Time.unscaledDeltaTime

- Time.smoothDeltaTime

- Time.timeScale

- Time.maximumDeltaTime

These properties each have their own scripting API documentation page, but it can help to see their descriptions and outputs in relation to each other to understand their appropriate uses.

Time.time indicates the amount of time elapsed since the player started, and so usually continuously and steadily rises. Time.deltaTime indicates the amount of time elapsed since the last frame, and so ideally remains fairly constant.

Both these values are subjective measures of time elapsed within your app or game. This means they take into account any scaling of time that you apply. So for example, you could set the Time.timeScale to 0.1 for a slow-motion effect (which indicates 10% of normal playback speed). In this situation the value reported by Time.time increases at 10% the rate of “real” time. After 10 seconds, the value of Time.time would have increased by 1. In addition to slowing down or speeding up time in your app, you can set Time.timeScale to zero to pause your game, in which case the Update method is still called, but Time.time does not increase at all, and Time.deltaTime is zero.

These values are also clamped by the value of the Time.maximumDeltaTime property. This means the length of any pauses or variations in frame rate reported by these properties will never exceed maximumDeltaTime. For example, if a delay of one second occurs, but the maximumDeltaTime is set to the default value of 0.333, Time.time would only increase by 0.333, and Time.deltaTime would equal 0.333, despite more time having actually elapsed in the real world.

The unscaled versions of each of these properties (Time.unscaledTime and Time.unscaledDeltaTime) ignore these subjective variations and limitations, and report the actual time elapsed in both cases. This is useful for anything that should respond at a fixed speed even when the game is playing in slow-motion. An example of this is UI(User Interface) Allows a user to interact with your application. More info

See in Glossary interaction animation.

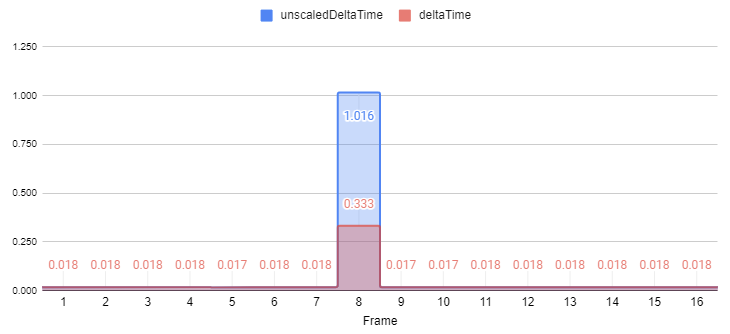

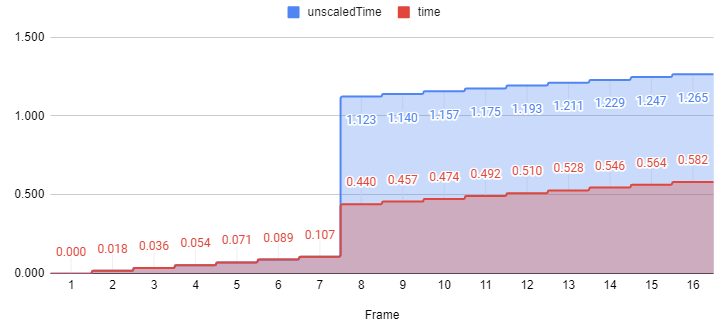

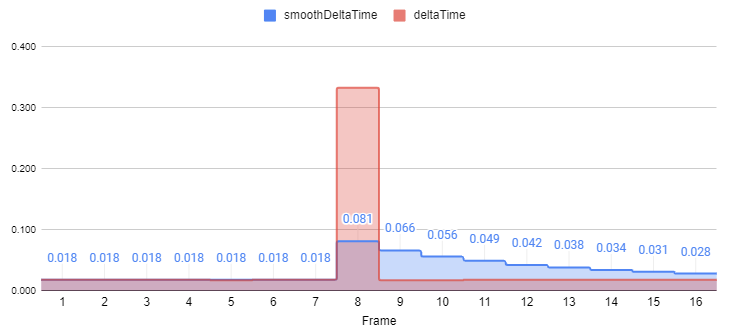

The table below shows an example of 16 frames elapsing one after another, with one large delay occuring half-way through, on a single frame. These figures illustrate how the various Time class properties report and respond to this large variation in frame rate.

| Frame | unscaledTime | time | unscaledDeltaTime | deltaTime | smoothDeltaTime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| 2 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| 3 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| 4 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| 5 | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.018 |

| 6 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| 7 | 0.107 | 0.107 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| 8 (a) | 1.123 (b) | 0.440 (c) | 1.016 (d) | 0.333 (e) | 0.081 (f) |

| 9 | 1.140 | 0.457 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.066 |

| 10 | 1.157 | 0.474 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.056 |

| 11 | 1.175 | 0.492 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.049 |

| 12 | 1.193 | 0.510 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.042 |

| 13 | 1.211 | 0.528 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.038 |

| 14 | 1.229 | 0.546 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.034 |

| 15 | 1.247 | 0.564 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.031 |

| 16 | 1.265 | 0.582 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.028 |

Frames 1 to 7 are running at a steady rate of approximately 60 frames per second. You can see both “time” and “unscaledTime” increasing steadily together, indicating that the timeScale during this example is set to 1.

Then on frame 8 (a), a large delay of just over one second occurs. This can happen when there is resource competition. For example, a code in the app blocks the main process while it loads a large amount of data from disk.

When a frame delay of larger than the maximumDeltaTime value occurs, Unity limits the value reported by deltaTime, and the amount added to the current time. The purpose of this limit is to avoid undesirable side-effects that might occur if the timestep exceeded that amount. If there was no limit, an object whose movement was scaled by deltaTime would be able to “glitch” through a wall in a game during a frame rate spike, because there would theoretically be no limit to how far an object could move from one frame to the next, so it could possibly jump from one side of an obstacle to another in a single frame without intersecting with it at all.

You can adjust the maximumDeltaTime value in the Time window, where it is labelled Maximum allowed timestep, as well as with the Time.maximumDeltaTime property.

The default maximumDeltaTime value is one third of a second (0.3333333). This means that in a game where movement is controlled by deltaTime, an object’s movement from one frame to the next is limited to the distance it could cover in a third of a second, regardless of how much time actually elapsed since the previous frame.

Looking at the data from the table above in graph form can help to visualise how these time properties behave in relation to each other:

You can see above, on frame 8, that unscaledDeltaTime (d) and deltaTime (e) differ in how much time they report has elapsed. Although a whole second of real time elapsed between frames 7 and 8, deltaTime reports only 0.333 seconds. This is because deltaTime is clamped to the maximumDeltaTime value.

Similarly, unscaledTime (b) has increased by approximately a whole second because the true (unclamped) value has been added, whereas time (c) has only increased by the smaller clamped value. The time value does not catch up to the real amount of time that has elapsed, and instead behaves as though the delay was only maximumDeltaTime in duration.

The Time.smoothDeltaTime property reports an approximation of the recent deltaTime values with all variations smoothed out according to an algorithm. This is another technique to avoid undesirably large steps or fluctuations in movement or other time-based calculations. In particular, those which fall below the threshold set by maximumDeltaTime. The smoothing-out algorithm cannot predict future variations, but it gradually adapts its reported value to smooth out variations in the recently elapsed delta time values, so that the average reported time remains approximately equivalent to the actual amount of time elapsed.

Time variation and the physics system

The maximumDeltaTime value also affects the physics system. The physics system uses the fixedTimestep value to determine how much time to simulate in each step. Unity tries to keep the physics simulation up-to-date with the amount of time that has elapsed and, as mentioned above, sometimes performs multiple physics updates per frame. However if the physics simulation fall too far behind, for example because of some heavy computation or a delay of some kind, the physics system may require a large number of steps to catch up with the current time. This large number of steps may then itself cause a further slow-down.

To avoid this cyclic feedback of slowing down due to attempting to catch up, the maximumDeltaTime value also acts as a limit on the amount of time the physics system will simulate between any given two frames.

If a frame update takes longer than maximumDeltaTime to process, the physics engineA system that simulates aspects of physical systems so that objects can accelerate correctly and be affected by collisions, gravity and other forces. More info

See in Glossary will not try to simulate any time beyond the maximumDeltaTime, and instead lets the frame processing catch up. Once the frame update has finished, the physics resumes as though no time has passed since it stopped. The result of this is that physics objects will not move perfectly in real time as they usually do, but will be slowed slightly. However, the physics “clock” will still track them as though they were moving normally. The slowing of physics time is usually not noticeable and is often an acceptable trade-off against gameplay performance.

Time Scale

For special time effects such as slow-motion, it’s sometimes useful to slow the passage of game time so that animations and time-based calculations in your code happen at a slower pace. Furthermore, you may sometimes want to freeze game time completely, as when the game is paused. Unity has a Time Scale property that controls how fast game time proceeds relative to real time. If you set the scale to 1.0, your in-game time matches real time. A value of 2.0 makes time pass twice as quickly in Unity (ie, the action will be speeded-up) while a value of 0.5 will slow gameplay down to half speed. A value of zero will make your in-game time stop completely. Note that the time scale doesn’t actually slow execution but instead changes the time step reported to the Update and FixedUpdate functions with Time.deltaTime and Time.fixedDeltaTime. Your Update function may be called just as often when you reduce your time scale, but the value of deltaTime each frame will be less. Other script functions aren’t affected by the time scale, so you can for example display a GUI with normal interaction when the game is paused.

The Time window has a property to let you set the time scale globally but it’s usually more useful to set the value from a script using the ScriptRef:Time-timeScale property:

//C# script example

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class ExampleScript : MonoBehaviour {

void Pause() {

Time.timeScale = 0;

}

void Resume() {

Time.timeScale = 1;

}

}

Capture frame rate

A special case of time management is where you want to record gameplay as a video. Since the task of saving screen images takes considerable time, the game’s normal frame rate is reduced, and the video doesn’t reflect the game’s true performance.

To improve the video’s appearance, use the Capture Framerate property. The property’s default value is 0, for unrecorded gameplay. For recording. When you set the property’s value to anything other than zero, game time is slowed and the frame updates are issued at precise regular intervals. The interval between frames is equal to 1 / Time.captureFramerate, so if you set the value to 5.0 then updates occur every fifth of a second. With the demands on frame rate effectively reduced, you have time in the Update function to save screenshots or take other actions:

//C# script example

using UnityEngine;

using System.Collections;

public class ExampleScript : MonoBehaviour {

// Capture frames as a screenshot sequence. Images are

// stored as PNG files in a folder - these can be combined into

// a movie using image utility software (eg, QuickTime Pro).

// The folder to contain our screenshots.

// If the folder exists we will append numbers to create an empty folder.

string folder = "ScreenshotFolder";

int frameRate = 25;

void Start () {

// Set the playback frame rate (real time will not relate to game time after this).

Time.captureFramerate = frameRate;

// Create the folder

System.IO.Directory.CreateDirectory(folder);

}

void Update () {

// Append filename to folder name (format is '0005 shot.png"')

string name = string.Format("{0}/{1:D04} shot.png", folder, Time.frameCount );

// Capture the screenshot to the specified file.

Application.CaptureScreenshot(name);

}

}

Using this technique improves the video, but can make the game much harder to play. Try different values of Time.captureFramerate to find a good balance.