コルーチン

A coroutine allows you to spread tasks across several frames. In Unity, a coroutine is a method that can pause execution and return control to Unity but then continue where it left off on the following frame.

In most situations, when you call a method, it runs to completion and then returns control to the calling method, plus any optional return values. This means that any action that takes place within a method must happen within a single frame update.

In situations where you would like to use a method call to contain a procedural animation or a sequence of events over time, you can use a coroutine.

However, it’s important to remember that coroutines aren’t threads. Synchronous operations that run within a coroutine still execute on the main thread. If you want to reduce the amount of CPU time spent on the main thread, it’s just as important to avoid blocking operations in coroutines as in any other script code. If you want to use multi-threaded code within Unity, consider the C# Job System.

It’s best to use coroutines if you need to deal with long asynchronous operations, such as waiting for HTTP transfers, asset loads, or file I/O to complete.

Coroutine example

As an example, consider the task of gradually reducing an object’s alpha (opacity) value until it becomes invisible:

void Fade()

{

for (float ft = 1f; ft >= 0; ft -= 0.1f)

{

Color c = renderer.material.color;

c.a = ft;

renderer.material.color = c;

}

}

In this example, the Fade method doesn’t have the effect you might expect. To make the fading visible, you must reduce the alpha of the fade must over a sequence of frames to display the intermediate values that Unity renders. However, this example method executes in its entirety within a single frame update. The intermediate values are never displayed, and the object disappears instantly.

To work around this situation, you could add code to the Update function that executes the fade on a frame-by-frame basis. However, it can be more convenient to use a coroutine for this kind of task.

In C#, you declare a coroutine like this:

IEnumerator Fade()

{

for (float ft = 1f; ft >= 0; ft -= 0.1f)

{

Color c = renderer.material.color;

c.a = ft;

renderer.material.color = c;

yield return null;

}

}

A coroutine is a method that you declare with an IEnumerator return type and with a yield return statement included somewhere in the body. The yield return nullline is the point where execution pauses and resumes in the following frame. To set a coroutine running, you need to use the StartCoroutine function:

void Update()

{

if (Input.GetKeyDown("f"))

{

StartCoroutine("Fade");

}

}

The loop counter in the Fade function maintains its correct value over the lifetime of the coroutine, and any variable or parameter is preserved between yield statements.

Coroutine time delay

By default, Unity resumes a coroutine on the frame after a yield statement. If you want to introduce a time delay, use WaitForSeconds:

IEnumerator Fade()

{

for (float ft = 1f; ft >= 0; ft -= 0.1f)

{

Color c = renderer.material.color;

c.a = ft;

renderer.material.color = c;

yield return new WaitForSeconds(.1f);

}

}

You can use WaitForSeconds to spread an effect over a period of time, and you can use it as an alternative to including the tasks in the Update method. Unity calls the Update method several times per second, so if you don’t need a task to be repeated quite so often, you can put it in a coroutine to get a regular update but not every single frame.

For example, you can might have an alarm in your application that warns the player if an enemy is nearby with the following code:

function ProximityCheck()

{

for (int i = 0; i < enemies.Length; i++)

{

if (Vector3.Distance(transform.position, enemies[i].transform.position) < dangerDistance) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

敵が数多く存在する場合は、この関数を毎フレーム呼び出しすると著しいオーバーヘッドが生じるかもしれません。しかし、コルーチンを使用して 1/10 秒ごとに呼び出すことができます。

IEnumerator DoCheck()

{

for(;;)

{

ProximityCheck();

yield return new WaitForSeconds(.1f);

}

}

This reduces the number of checks that Unity carries out without any noticeable effect on gameplay.

Stopping coroutines

To stop a coroutine, use StopCoroutine and StopAllCoroutines. A coroutine also stops if you’ve set SetActive to false to disable the GameObject the coroutine is attached to. Calling Destroy(example) (where example is a MonoBehaviour instance) immediately triggers OnDisable and Unity processes the coroutine, effectively stopping it. Finally, OnDestroy is invoked at the end of the frame.

Note: If you’ve disabled a MonoBehaviour by setting enabled to false, Unity doesn’t stop coroutines.

Analyzing coroutines

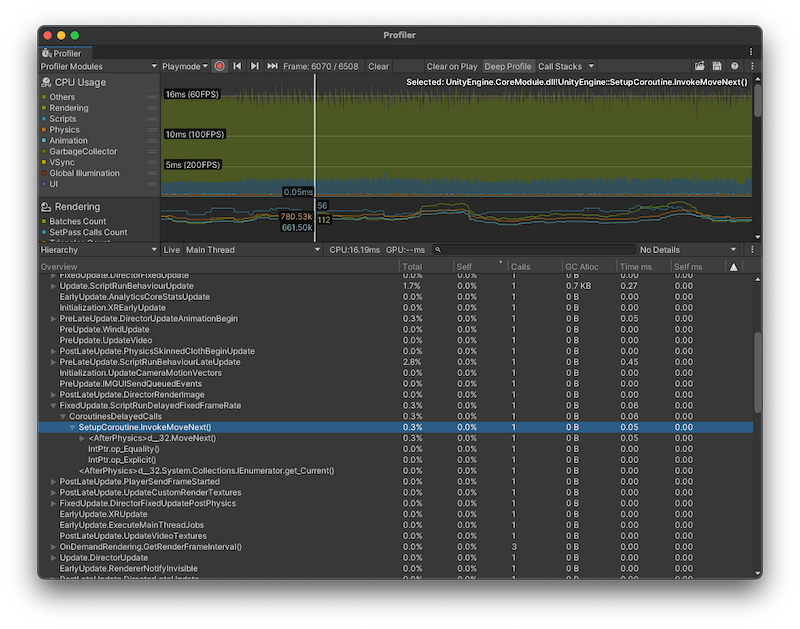

Coroutines execute differently from other script code. Most script code in Unity appears within a performance trace in a single location, beneath a specific callback invocation. However, the CPU code of coroutines always appears in two places in a trace.

All the initial code in a coroutine, from the start of the coroutine method until the first yield statement, appears in the trace whenever Unity starts a coroutine. The initial code most often appears whenever the StartCoroutine method is called. Coroutines that Unity callbacks generate (such as Start callbacks that return an IEnumerator) first appear within their respective Unity callback.

The rest of a coroutine’s code (from the first time it resumes until it finishes executing) appears within the DelayedCallManager line that’s inside Unity’s main loop.

This happens because of the way that Unity executes coroutines. The C# compiler auto generates an instance of a class that backs coroutines. Unity then uses this object to track the state of the coroutine across multiple invocations of a single method. Because local-scope variables within the coroutine must persist across yield calls, Unity hoists the local-scope variables into the generated class, which remain allocated on the heap during the coroutine. This object also tracks the internal state of the coroutine: it remembers at which point in the code the coroutine must resume after yielding.

Because of this, the memory pressure that happens when a coroutine starts is equal to a fixed overhead allocation plus the size of its local-scope variables.

The code which starts a coroutine constructs and invokes an object, and then Unity’s DelayedCallManager invokes it again whenever the coroutine’s yield condition is satisfied. Because coroutines usually start outside of other coroutines, this splits their execution overhead between the yield call and DelayedCallManager.

You can use the Unity Profiler to inspect and understand where Unity executes coroutines in your application. To do this, profile your application with Deep Profiling enabled, which profiles every part of your script code and records all function calls. You can then use the CPU Usage Profiler module to investigate the coroutines in your application.

It’s best practice to condense a series of operations down to the fewest number of individual coroutines possible. Nested coroutines are useful for code clarity and maintenance, but they impose a higher memory overhead because the coroutine tracks objects.

If a coroutine runs every frame and doesn’t yield on long-running operations, it’s more performant to replace it with an Update or LateUpdate callback. This is useful if you have long-running or infinitely looping coroutines.